“Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” one of the most momentous sociological and literary achievements at the onset of the twentieth century, has markedly affected my life and work by virtue of its implication that the role of art isn’t just to show life as it is but to show life as it should be. In this sacred song, James Weldon Johnson fused the sufferings, pathos, hopes, and dreams of a people to create an enduring and material work of art. In essence, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” symbolizes the power of combining art with the human struggle.

—Harry Belafonte, singer, songwriter, activist, and actor, published in Lift Every Voice and Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem; 100 Years, 100 Voices, by Julian Bond and Dr. Sondra Kathryn Wilson

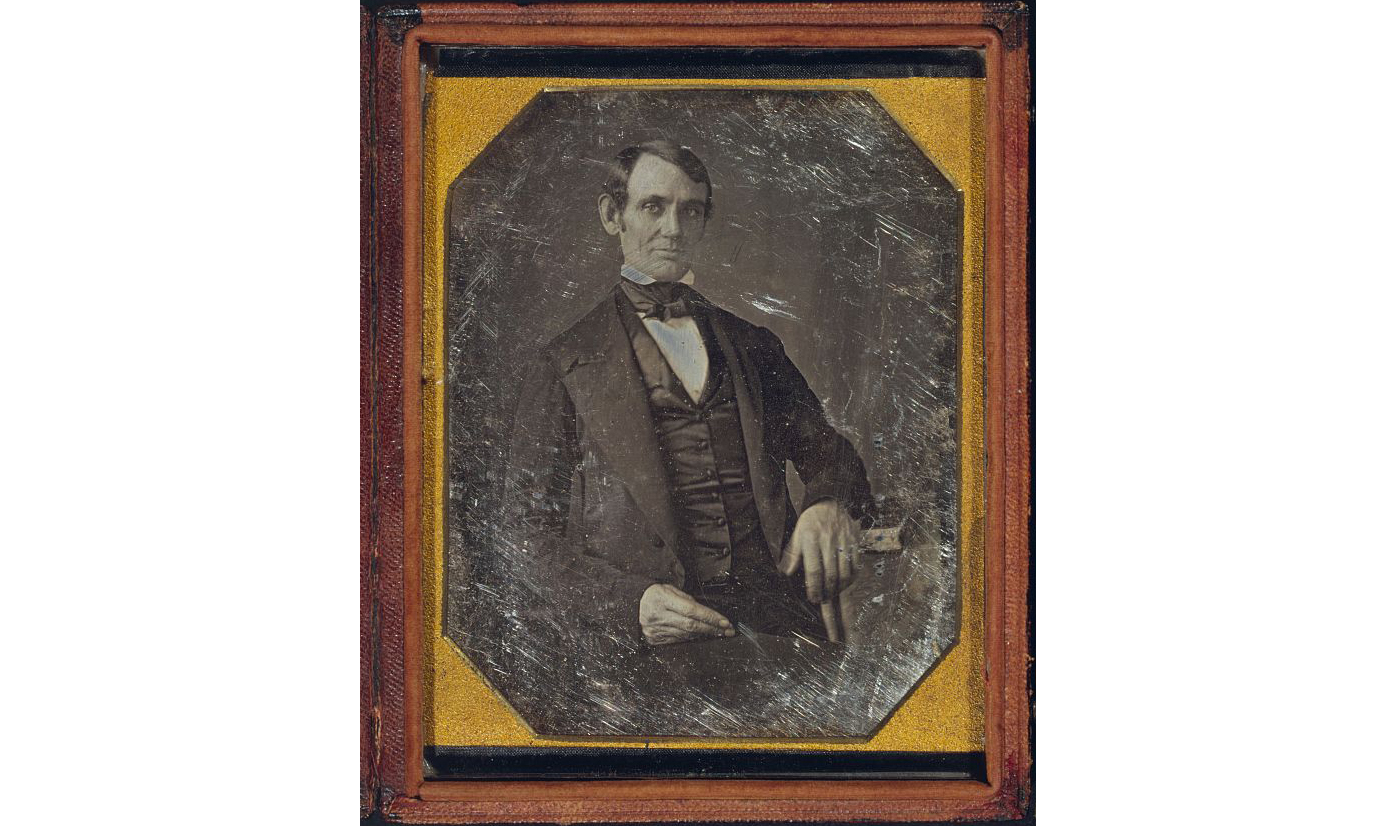

Some songs flow out of an artist as if by divine inspiration; some songs must be arduously wrung out of the creative mind like the last drops of water from a damp towel. The song “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” often referred to as America’s Black National Anthem, was composed in 1900 by artists who faced a bit of both experiences. Written by two black men to celebrate Abraham Lincoln’s birthday at a segregated school in Florida, the song was composed, performed, then promptly forgotten about by its creators — but the song lived on, spread from person to person, until it became so powerful that within 20 years of its debut it was declared the Negro National Hymn.

Today, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (now usually titled more modernly as “Lift Every Voice and Sing”) is one of the most cherished songs of the African American Civil Rights Movement; it was added to the National Recording Registry in 2016, and it has been performed and recorded countless times at seminal events by some of the greatest artists who ever lived.

Strangely, most people in the US have never heard of it and don’t know there even is a Black National Anthem; those few people who are aware of the song know little about it. But the song’s conception and history are definitely worth knowing, not just for its cultural value — which is immense — but for its inspiration, its insight into the art of songwriting, and for what it says about the indefatigable power of music.

“The lines of this song repay me in an elation, almost of exquisite anguish, whenever I hear them sung by Negro children,” stated James Weldon Johnson, who wrote the lyrics, while his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, composed the music. “Nothing that I have done has paid me back so fully in satisfaction as being the part creator of this song.”

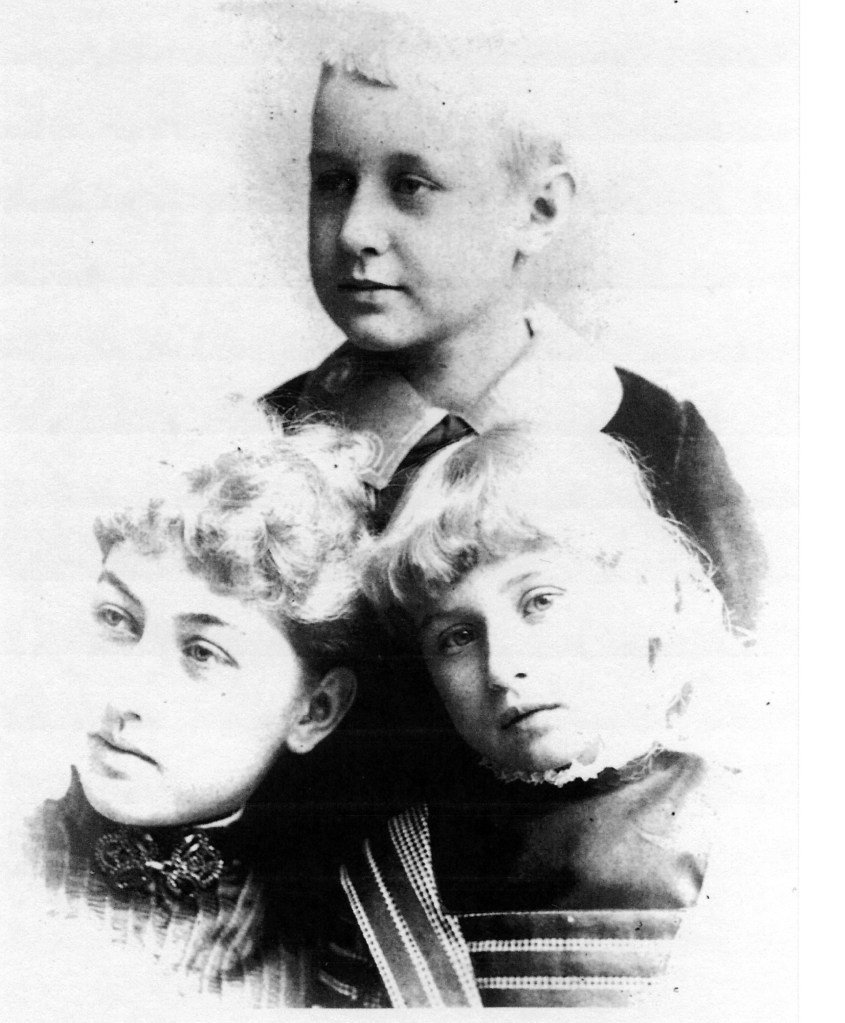

The Johnson Brothers

The Johnson brothers today are considered two of the most important figures in early 20th century Black intellectual and artistic circles — and they would be considered so even if they had not written “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

James Weldon Johnson

James was an author, lyricist, poet, diplomat, attorney, and leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida, he was trained in music and other subjects by his mother, who was a schoolteacher. James graduated from Atlanta University with undergraduate (1894) and graduate (1904) degrees, and later studied at Columbia University. While teaching school early in his career, he began studying law and in 1898 became the first Black man admitted to the Florida Bar since Reconstruction.

During this period, James was also a poet, writer, and lyricist, and in 1901 he and his brother John Rosamond Johnson (who went by J. Rosamond Johnson) went to New York, where they wrote some 200 songs for the Broadway musical stage. In New York, James began making connections to influential members of the Black community. After serving as treasurer for the Colored Republican Club, Johnson was appointed the US consul in Venezuela by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906. Three years later, Johnson was moved to Nicaragua to serve as consul there. During this time, Johnson continued to write poetry and anonymously published his novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912), a story of a young biracial man living in the post-Reconstruction era.

James eventually left the diplomatic field to join the civil rights movement as a leader in the NAACP. He started as a field secretary in 1916 and ultimately became executive secretary of the organization.

Throughout the 1920s, James supported and promoted the Harlem Renaissance. According to his official NAACP biography, “Johnson believed Black Americans should produce great literature and art in order to demonstrate their equality to whites in terms of intellect and creativity.” In addition to his Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, James authored three other books of nonfiction and three collections of poetry; he also edited three poetry anthologies and taught creative writing at Fisk University in Nashville.

He died in 1938 at the age of 67 in a car accident.

John Rosamond Johnson

John Rosamond Johnson had a varied career as a pianist, songwriter, producer, soldier, singer, and actor. Born in 1873 in Jacksonville, Florida, J. Rosamond began playing the piano at age four. He studied at the New England Conservatory and, by the end of the 19th century, was teaching schoolchildren in the Jacksonville region.

John moved to New York City in 1900 with his brother James to find success on Broadway. According to the Library of Congress, John was one of the more important figures in black music in the first part of the 20th century. After contributing a song to Williams and Walker’s Sons of Ham (1900), Johnson created a vaudeville act and wrote songs with Robert Cole. This partnership (which often also included James in the songwriting) lasted until Cole’s death in 1911. Besides crafting a sophisticated vaudeville style, Cole and Johnson produced two popular all-black operettas on Broadway, The Shoo-Fly Regiment (1907) and The Red Moon (1909). In addition to musicals, John wrote popular songs and works for piano.

Along with his musical work, John performed important work in literature, education, and the military. At the onset of World War I, he put his performing career on hold and accepted a commission as a second lieutenant in the 15th New York National Guard Regiment, which consisted mostly of African Americans. The unit spent more days in the frontline trenches than any other American unit, also suffering the most losses.

After the war, John continued writing and performing. He also worked as a literary editor, collecting four anthologies of traditional African American songs — two of which he compiled with his brother James: The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925) and The Second Book of Negro Spirituals (1926). John also founded a school in Harlem called the New York Music School Settlement for Colored People and served as its music director.

He died in New York City in 1954.

The Song and Its Creation

“Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is a hymn of agony and hope for Blacks in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, of overcoming the dark past of slavery and facing the future with a faithful optimism and patriotic loyalty:

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

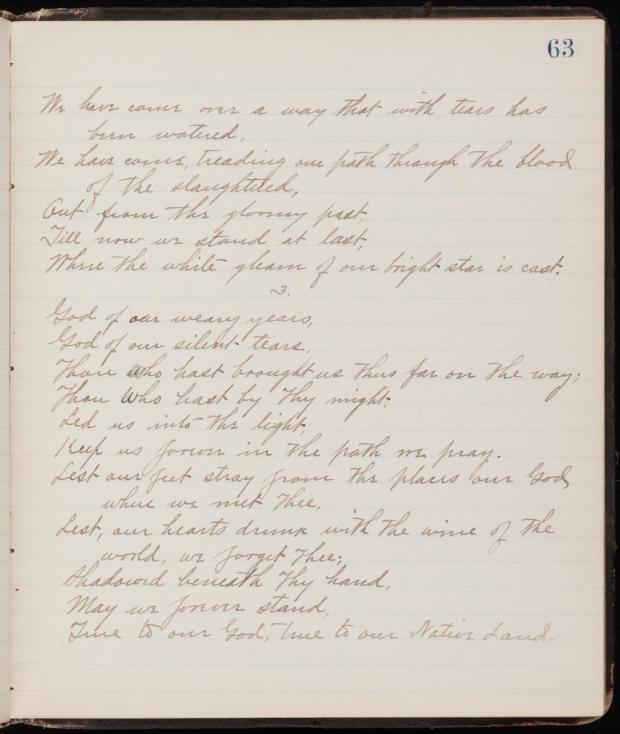

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.(From Saint Peter Relates an Incident by James Weldon Johnson. Copyright © 1917, 1921, 1935 James Weldon Johnson, renewed 1963 by Grace Nail Johnson.)

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who hast by Thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our God,

True to our native land.

James Weldon Johnson wrote and spoke about the creation of the song multiple times, but the most detailed version is from his 1933 autobiography, Along This Way:

A group of young men decided to hold on February 12 a celebration of Lincoln’s birthday. I was put down for an address, which I began preparing; but I wanted to do something else also. My thoughts began buzzing round a central idea of writing a poem on Lincoln, but I couldn’t net them. So I gave up the project as beyond me; at any rate, beyond me to carry out in so short a time; and my poem on Lincoln is still to be written. My central idea, however, took on another form. I talked over with my brother the thought that I had in mind, and we planned to write a song to be sung as part of the exercises. We planned, better still, to have it sung by schoolchildren — a chorus of five hundred voices.

I got the first line:—Lift ev’ry voice and sing. Not a startling line; but I worked along grinding out the next five. When, near the end of the first stanza, there came to me these lines

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has brought us.

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

the spirit of the poem had taken hold of me. I finished the stanza and turned it over to Rosamond.

In composing the two other stanzas I did not use pen and paper. While my brother worked at the musical setting I paced back and forth on the front porch, repeating the lines over and over to myself, going through all the agony and ecstasy of creating. As I worked through the opening and middle lines of the last stanza:

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way,

Thou who has by thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray;

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee…

I could not keep back the tears, and made no effort to do so. I was experiencing the transports of the poet’s ecstasy. Feverish ecstasy was followed by that contentment — some sense of serene joy — which makes artistic creation the most complete of all human experiences.

After the lyrics were done and Rosamond had completed composing the music, the brothers sent the song to their publishers in New York, Edwin B. Marks Company, asking for enough mimeographed copies for the children’s chorus performance on February 12. The song was sung at the event, it went very well, and the two brothers both moved away from Jacksonville, Florida, and forgot all about their composition. But, as James recalled later:

The schoolchildren of Jacksonville kept singing the song; some of them went off to other schools and kept singing it; some of them became schoolteachers and taught it to their pupils. Within twenty years the song was being sung in schools and churches and on special occasions throughout the South and in some other parts of the country. Within that time the publishers had recopyrighted it and issued it in several arrangements. Later it was adopted by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and is now quite generally used throughout the country as the ‘Negro National Hymn’. …

Nothing that I have done has paid me back so fully in satisfaction as being the part creator of this song. I am always thrilled deeply when I hear it sung by Negro children. I am lifted up on their voices, and I am also carried back and enabled to live through again the exquisite emotions I felt at the birth of the song. My brother and I, in talking, have often marveled at the results that have followed what we considered an incidental effort, an effort made under stress and with no intention other than to meet the needs of a particular moment. The only comment we can make is that we wrote better than we knew.

“Lift Ev’ry Voice” – History and Legacy

The subsequent history of the song “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” is alive and permanent:

The song was first recorded in 1923 by the male gospel group Manhattan Harmony Four.

It was subsequently featured in the 1939 film Keep Punching and then in the 1989 film Do the Right Thing (with a 30-second clip of the song played on solo saxophone by Branford Marsalis).

The song eventually was adopted by NAACP and prominently used as a rallying cry during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

In 2009, the Rev. Joseph Lowery used the song’s third stanza to begin his benediction at the inauguration for America’s first Black president, Barack Obama.

In 2016, the song was sung at the conclusion of the opening ceremonies of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, and was also added to the National Recording Registry.

Since 2020, the song has seen a new resurgence in popularity — and a growth in the awareness of its general existence — due to the massive expansion of the Black Lives Matter movement in the Unites States in response to the murder of George Floyd.

Links For More Information

Want to learn more? Check out these resources:

- Julian Bond and Sondra Kathryn Wilson, Lift Every Voice and Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem; 100 Years, 100 Voices

- Imani Perry, May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem

- Purchase the sheet music from Edward B. Marks Company

- www.jamesweldonjohnson.com

- www.jrosamondjohnson.org